British Library Sound Archive - Anglo-Colombian Recording Expedition, 1960-1961

Selection and mix by Andrea Zarza Canova. Thanks to Brian Moser for his ideas and for agreeing to have these recordings shared on NTS Radio. This programme is dedicated to all of the unnamed performers who appear in the sound recordings and to the memory of Dr. Donald Tayler (1931-2012) who recorded and documented them.

“It was as itinerant collectors of music that Brian Moser and myself, sometimes accompanied by others, set out to visit a number of Colombian Indian tribes, recording what we could of a music which we believed was fast disappearing. Inevitably our work tended to be precipitous and rudimentary. We had no chance to learn any of the tribal languages, and each tribe spoke its own. Seldom were we able to record the music within the context of its rite and frequently we found it difficult to record at all for a number of reasons, while our own descriptions and noting of what we did see naturally left much to be desired.” (Tayler, The Music of Some Indian Tribes of Colombia )

Brian Moser and Donald Tayler (1931-2012) met whilst studying at Cambridge University. After their studies, they went separate ways: Brian Moser left for Colombia in 1959 to work as a geologist within a Cambridge expedition to the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy in Boyacá, Colombia, where the flora was uncharted and there were no recorded ascents of peaks. Donald Tayler had gone to New Guinea to work for a British engineering company overseeing the construction of the foundations of a hydro-electric dam. Brian Moser stayed on in Colombia after the expedition, and at the recommendation of Dr. Gerardo Reichel Dolmatoff from the Colombian Institute of Anthropology, he met Richard Evans Schultes, an American ethnobotanist specialised in hallucinogenic plants popularly known for his book Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers (1979), co-authored with Albert Hoffmann. According to Moser, it was Schultes who gave him the idea to go to map the River Piraparaná, and this four-month canoe trip would be the second stage of the Anglo-Colombian Recording Expedition 1960-61.

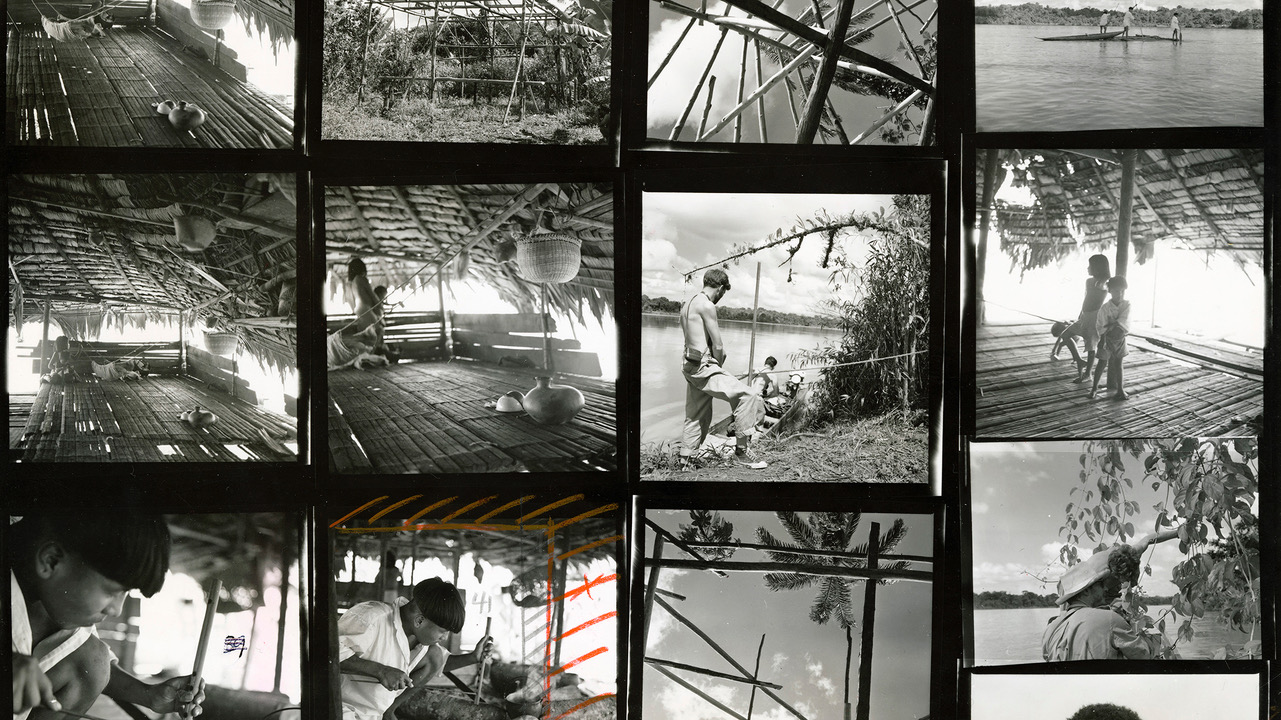

Brian Moser was 25 and Donald Tayler was 29 when they began their fourteen month journey in Colombia, setting out to visit six different Indian groups “with the main purpose of recording music and making an ethnographical collection for the British Museum. Studies were also made in the use of narcotics and stimulants, in primitive agriculture and aspects of material culture.” (Moser and Tayler, Tribes of the Piraparaná).

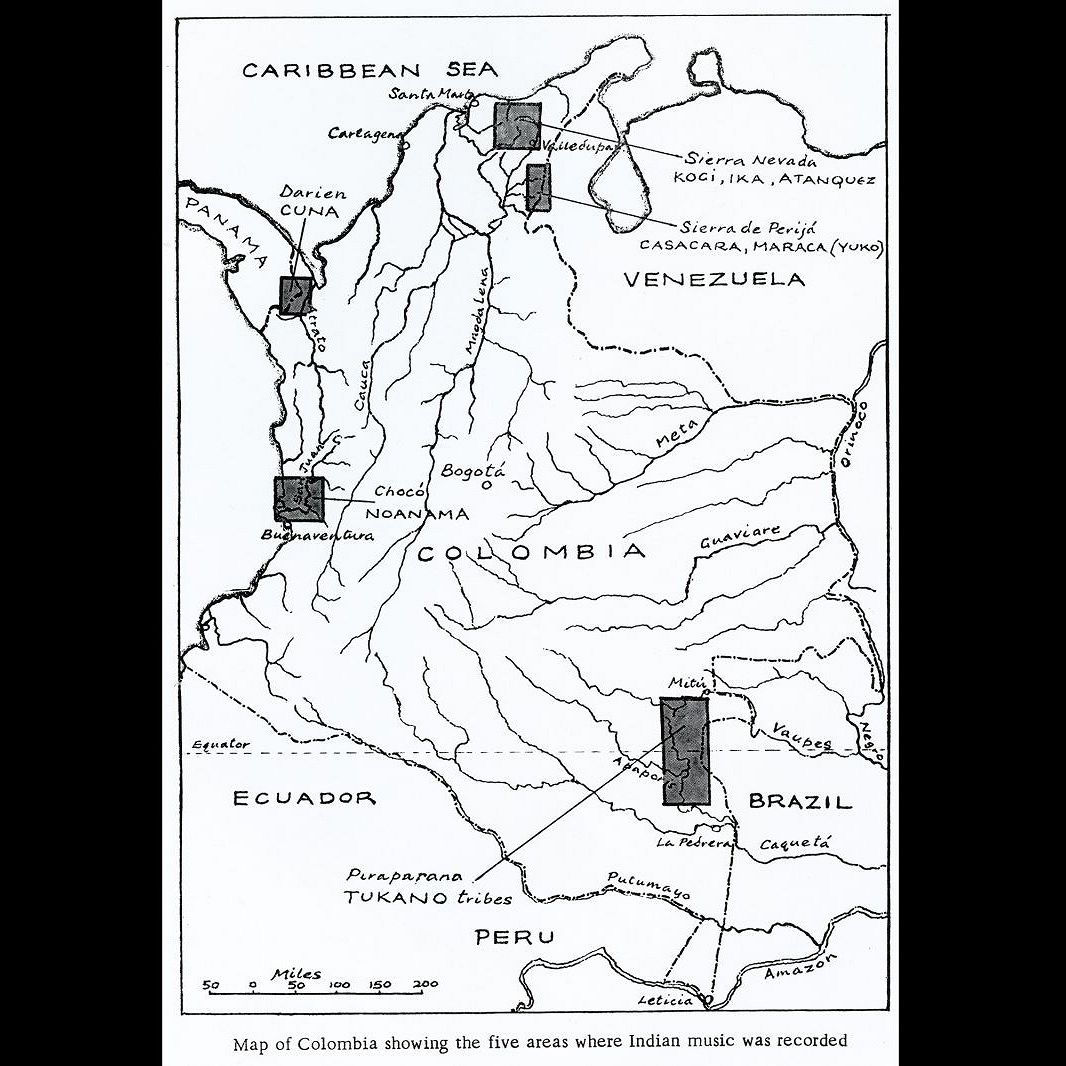

Moser and Tayler certainly recorded music during rites and ceremonies—such as the dances from the Piraparaná malocas or the sacred chanting within important coca-taking sessions—but they did not set up special recording sessions and diminish the spontaneity or quality of that which was being recorded. Though they had no previous experience making ethnomusicological recordings, they had expertise in making collections. During the expedition they visited the Noanamá, who lived in the delta of the Río San Juan on the Pacific seaboard, the Tukano groups of the Río Piraparaná, the Kogi and Bintukua (Chibcha) in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, the Guajiro (Arawak) in the Guajira Peninsula, the Casacará and Maraca who are both sub-groups of the Yuco-Motilon (Carib) living in the Sierra de Perijá and the Cuna (Carib) in the Gulf of Darien on the border with Panamá.

The trip was supported by institutions in England such as the British Museum, who currently hold a vast collection of ethnographic objects from the trip ranging from baskets and arrows to musical instruments such as perforated conch shells; the Royal Geographical Society; the Isaac Wolfson Foundation; the Frederick Soddy Trust and the British Institute of Recorded Sound, predecessor of what is today the British Library Sound Archive. It was because of the British Institute of Recorded Sound that the expedition took a sonic focus, Patrick Saul who was the director, facilitated a Nagra Kudelski (reel-to-reel tape recorder) and his friend, John Levy, gave Donald training. In Colombia, they were supported by many specialists such as Dr. Medem at the Institute of Natural Sciences but of course, as Moser and Tayler themselves state in the liner notes to the first commercial release of these recordings, The Music of Some Indian Tribes of Colombia, “Our greatest debt is however to our Colombian Indian hosts to whom no acknowledgement is adequate for their hospitality, generosity and patience in allowing us to live with them and to record a little of their music.”

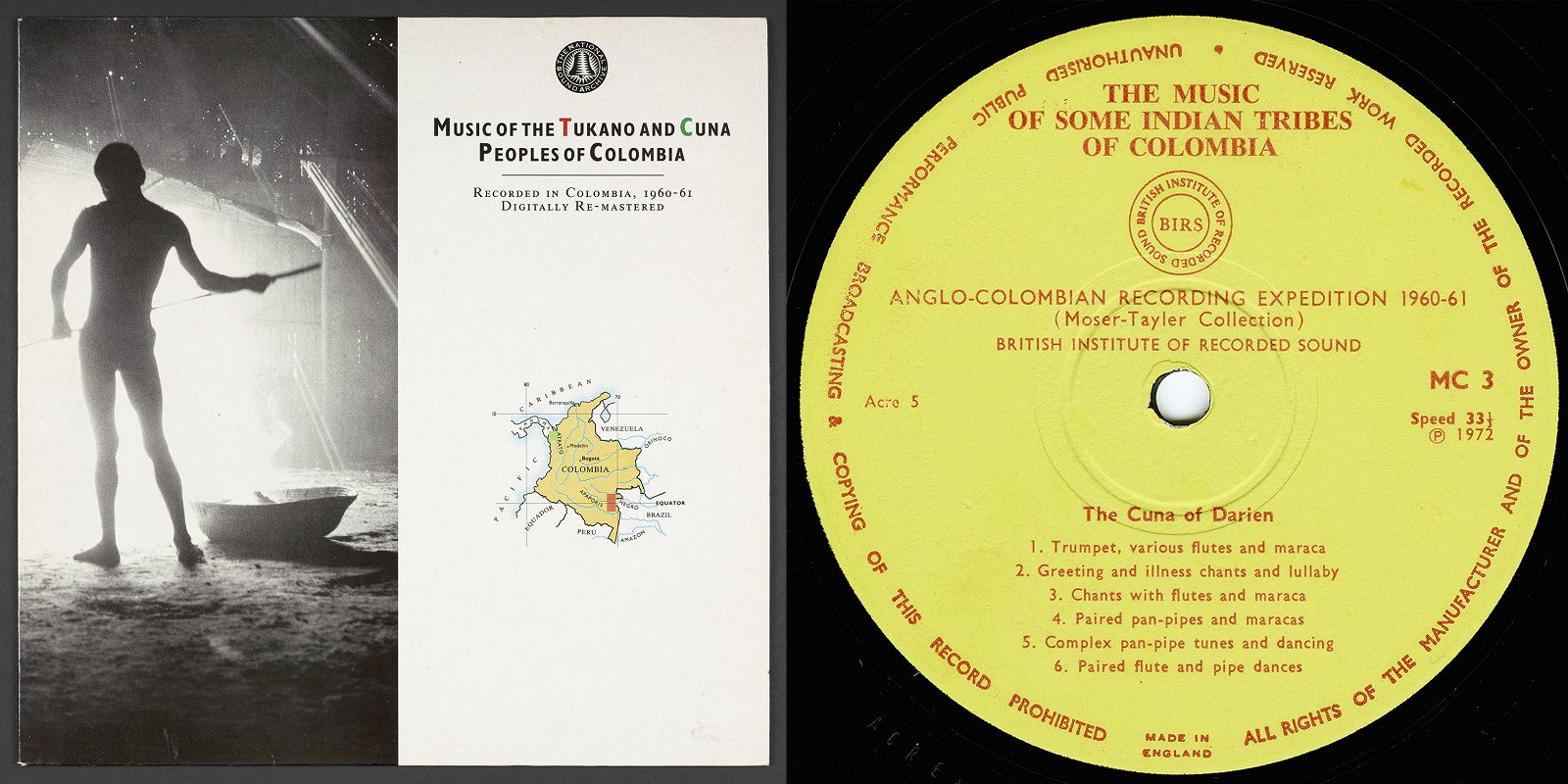

Centre label of box-set release of the Anglo-Colombian Recording Expedition recordings by the British Institute of Recorded Sound, LP cover of re-issue by Rogue Records and the National Sound Archive.

What we can hear in this hour-long programme is a very small selection taken from the 80 hours of recordings gathered throughout the course of the expedition. The recordings were chosen to showcase the variety of songs, voices, languages and landscapes encountered, with the aim of drawing the listener into the spaces Moser and Tayler experienced. A detailed track-listing cobbled together from publications by Donald Tayler and recent e-mail exchanges with Brian Moser, follows below for the curious listener –

“It may be suggested that music is music and that words add little; far better that we should have left an analysis of the sound to more capable hands, but this we hope will be done. Our thesis is that without some knowledge of the background of this tribal music we cannot too hastily interpret the sounds—at least we can do so but it will bring us no closer to an understanding of what it means to the people who perform it.” (Tayler, The Music of Some Indian Tribes of Colombia )

Part 1 – 00:00:00 – [British Library reference number C207/32, excerpt]

Full recording available online

Casacará Music. Recorded in the northern Sierra of Perijá, Colombia

The opening songs were recorded in a small village in the northern Sierra of Perijá, where two Indian groups, Casacará and Maraca, both sub-groups of the Bari Motilón, thought to be of Carib origin, live in close proximity.

Brian Moser and Donald Tayler spent time with both the Casacará and the Maraca during their expedition. In an email, Brian Moser elaborated on this: “We stayed with both the Casacará and the Maraca, finding them both friendly but still war-like, mainly between themselves. They are highly musical, with axe-head flutes made from a balsa-wood tube onto which is attached a large beeswax head with a tiny reed inserted into the axe-head. They also play musical bows, panpipes, flutes – some made from human bones, even a missionary’s tibia had been used. These instruments were played extensively when a person died and then later in the important out-burial ceremonies.”

This first song is a song duet called shatle sung in unison by two men. You can hear a four-note melody, which in other recordings of Casacará music, is repeated on the pipe as flute and voice are often interchangeable. Then the clear singing voice of a lone man, who with a rooster crowing in the background, delivers another four-note melody.

00:02:12 – [British Library reference number C207/31]

Excerpt from tape; full recording available online

At the start of this excerpt you can hear Brian Moser, saying “Espera, espera…”, Spanish for “Wait, wait…”, before the group of men begins whistling. This is a common Casacará tune, whistled and sung by men as they go to their gardens or visit another village. The majority of Casacará songs begin with whistling the tune, which in turn is then sung. Some Casacará songs also end with whistling. Usually the songs last for at least one minute, and may continue for four or five.

“Though this is considered a “walking song” it is important to note that it is possibly misleading to differentiate the songs as walking or hunting or otherwise, as these are not necessarily strict categories, or regarded as such by the Yuko themselves. It is possible that vowelling and humming of many of these songs indicates, as Dolmatoff suggests, that the word traditions are being forgotten, but it could equally indicate those songs which have been borrowed from another group whose dialect or language is unfamiliar to them. Or equally the melody and style of song may be more important than the words.” (Tayler, The Music of Some Indian Tribes of Colombia)

The last part of this sequence dedicated to Casacará music features a few drinking tunes, combining song and speech, sung by men. The words “Yakono wap se…” act as a reminder for friendliness during chicha drinking parties, occasions when fighting often breaks out, particularly when members of other villages or groups are presents.

Part 2 – 00:05:28 – [British Library reference number C207/56]

Excerpt from tape; full recording available online

Tukano Canoe burning. Recorded in Amazonas, Colombia

“As with most Amazonian tribes, the Tukano have no central authority or chieftainship. The malocas form autonomous units, only the headmen of these communal dwellings—in which live two or three interrelated families—having any authority. In the past, groups have been known to unite to fight a common enemy; a powerful headman at the turn of the century organized a small army from a number of malocas to kill rubber collectors and any Indians found cooperating with them.[…] The men build the new malocas, cut and burn the plantations, fish and hunt. But it is the task of the woman to provide the daily food; she plants the manioc, harvests and prepares it, she makes the pottery and hammocks and tends the children. To her falls the hardest work of their daily lives.” (Moser and Tayler, Tribes of the Piraparaná)

Part 3 – 00:07:43 – [British Library reference number C207/21]

Excerpt from tape; full recording available online

Drumming recorded during the third Fiesta del Mar in Santa Marta, Magdalena, Colombia

Part 4 – 00:10:33 – [British Library reference number C207/22]

Excerpt from tape; full recording online

Sound effects and music in house in Santa Marta, Magdalena, Colombia

Part 5 – 00:15:52 – [British Library reference number C207/23, excerpt]

Excerpt from tape; full recording available online

Conjunto Tejicondor, during the third Fiesta del Mar en la ciudad de Santa Marta, Magdalena, Colombia

We hear a Spanish speaker announcing the arrival of the musical group by airplane – “En estos momentos está aterrizando en el aeropuerto Simón Bolívar, el avión colombiano HK793, de líneas aéreas Taxader, con los integrantes del conjunto folclórico de Tejicondor, procedentes de la ciudad de Medellín. Este grupo artístico viene a las festividades de la tercera fiesta del mar en la ciudad de Santa Marta, que, muy bienvenidos”.

00:16:25 – [British Library reference number C207/19, excerpt]

Excerpt from tape; full recording available online

Conjunto Tejicondor performs in Santa Marta, Magdalena

Part 6 – 00:18:49 – [British Library reference number C207/25, excerpt]

Excerpt from tape; full recording available online

Rafael Escalona performs Vallenato Las Golondrinas at his home in Valledupar, César

In the late 1950’s Rafael Escalona together with a small group started to compose and sing a new range of contemporary songs relating to local events and people around Valledupar and the countryside where he lived. These songs gained immediate popularity throughout Colombia and Escalona himself became a household name. This recording was made in his home in Valledupar in June 1961 when Donald Tayler and Brian Moser recorded him “throughout a whole night of merriment, over many a bottle of beer and aguardiente” (Brian Moser, e-mail). If you listen closely to the lyrics in Spanish, you will hear Rafael Escalona dedicate the song to Donald who comes from far away, from the country of fog, London, a grand and friendly city, to share with us these moments of tenderness and scientific investigation, doing us a great honour, to which we will contribute as best as we possibly can…

Part 7 – 00:24:08 – [British Library reference number C207/2, excerpt]

Excerpt from tape; full recording available online

Bintukua vocabulary, recorded in San Sebastian De Rábago, Sierra Bintukua, Colombia

In this recording we can hear a recitation of Bintukua vocabulary and its equivalent Spanish words, recited between Don Samuel Martínez and an unnamed Bintukua woman. “Near the Mission there was a white-walled village which like San Miguel seemed almost deserted. There was only the office of Don Samuel and the shop belonging to his nephew who sold everything from tinned meat and porridge oats to medicines, shoes and wool, presumably to the Bintukua. Don Samuel was the local Comisario, he had retired many years before but the Indians had requested that he should come back. He spoke their language fluently and seemed to understand them. He was the only official contact between them and the Government.” (Moser, Tayler, The Cocaine Eaters)

Part 8 – 00:28:39 – [British Library reference number C207/6, excerpt]

Excerpt from tape; full recording available online

Antonio Crespo plays La Campanuca in San Sebastián de Rábago, Pueblo Bello, César

“Recording of flute with attached quill airduct. A larger flute than the Kogi one, with thread binding at intervals down the length of the cane. One of the five-fingers is played with the thumb. This tune called ‘La Campanuca’ is played by Antonio Crespo, an Ika Indian at the village of San Sebastián de Rábago in the southern sierra.” (Tayler, The Music of Some Indian Tribes of Colombia)

00:31:23 – [British Library reference number C207/7, excerpt]

Excerpt from tape; full recording available online

Kogi paired flutes with maraca rhythms, recorded in San Miguel, Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta

Part 9 – 00:35:14 – [British Library reference number C207/31, excerpt]

Excerpt from tape; full recording available online

Casacara dance for first fruits or maize called Wertrape

“Dance for first fruits or maize called Wertrape, in which two women, one voice being much closer, sing or hum softly to themselves as they move with their heads lowered on baskets strapped to the men’s foreheads, who in turn, sing rhythmic staccato shouts. Usually there would be many more dancers and singers.” (Tayler, The Music of Some Indian Tribes of Colombia)

Part 10 – 00:37:45 – [British Library reference number C207/42, excerpt]

Excerpt from tape; full recording available online

Soundscape of Casacara villages

Part 11 – 00:41:04 – [British Library reference number C207/27, excerpt]

Excerpt from tape; full recording available online

Yomaikut, chicha or drinking song recorded in the northern Sierra de Perijá

“Chicha or drinking songs called Yomaikut, sung or hummed first by the women, with the men joining in towards the end. These songs are also dances, referred to in the text as Naniwatro, in which the phrases are interspersed with pronounced foot stamping, and jumping, by a line of women as they move towards, then away again, from a similar line of men. This song, like many others, may be danced on various festival occasions and particularly during the death ceremonial.” (Tayler, The Music of Some Indian Tribes of Colombia)

Part 12 – 00:46:33 – [British Library reference number C207/47, excerpt]

Excerpt from tape; full recording available online

Coca-mortar rhythm in Tukano maloca, recorded in the middle Piraparaná

“Coca pounding in a large wooden vertical mortar is a sound common and familiar to all Tukano malocas at any time of day or night, and, although strictly speaking not a musical instrument, it has a pleasing mellow sound and rhythm. Whether by coincidence or design it frequently accompanies songs, pan-pipe tunes and tortoise-shell rubbing with its constant rhythm.” (Tayler, The Music of Some Indian Tribes of Colombia)

00:51:02 Antonio, a Taiwano man, sings to himself while cutting a new pan-pipe, recorded in the middle Piraparaná

“A Taiwano sings to himself as he cuts a new pan-pipe, with coca pounding in the background. The song ends in hissing; often Tukano hiss or whistle at the end of a song. Sung by Antonio at the Taiwano maloca on the middle Piriparaná.” (Tayler, The Music of Some Indian Tribes of Colombia)

00:52:40 Two tortoise-shell ‘goos’, with pan-pipe accompaniment played by Pedro, recorded in the middle Piraparaná

“The sounds of this strangely lugubrious instrument reverberate and echo around the maloca interiors which act as resonators, while the sound seems to linger on long after the performers have stopped. They do not seem to have any particular ceremonial or religious attachment, but are played for enjoyment. This could account for their relative scarceness in an area where they have been frequently reported in the past, but which is now changing fairly rapidly, under the influence of rubber gathering, traders, and more recently, the missions. Played at the Tatuya maloca of the headmen, Pedro, on the middle Piriparaná.” (Tayler, The Music of Some Indian Tribes of Colombia)

Part 13 – 00:55:01 – [British Library reference number C207/81]

Excerpt from tape; full recording available online

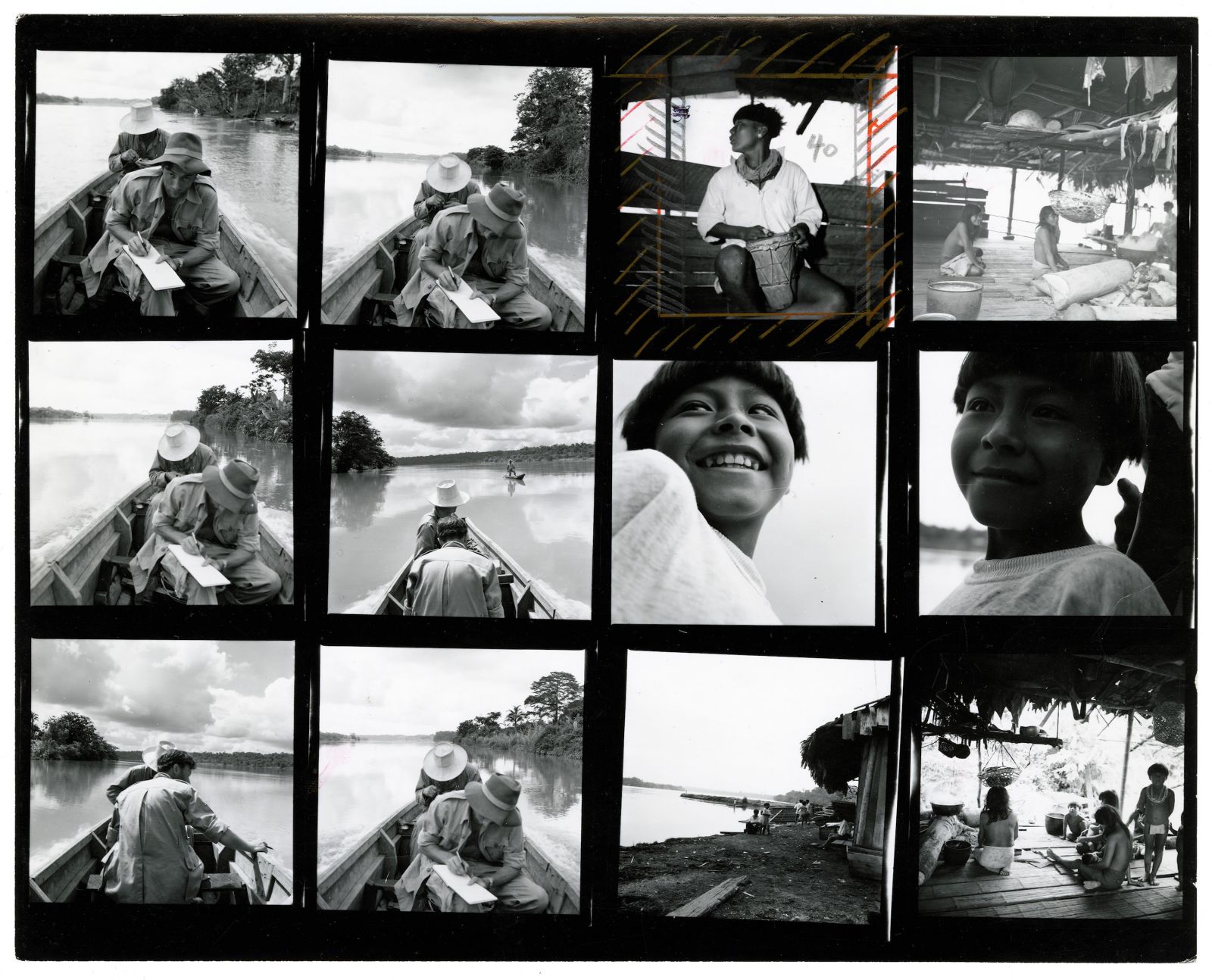

Noanamá (Choco) man, Davee, and wife sing songs from canoe, recorded near Cabeceras, lower Río San Juan

“This music from the lower Río San Juan includes both Chocó Indian (Noanamá) and Chocó Negro examples, with the emphasis placed on what may remain of the archaic pre-Colombian forms of Indian music and further examples of adaptations to contemporary African and European influences. A great amount of Noanamá music we recorded consisted of men and women´s solo and choral songs […] songs which might be sung at any time of day or night or night, in garden, canoe, or house, and which contrary to our recordings among other groups, seemed to have no specific ceremonial or religious significance, apart from evident enjoyment and pleasure.” (Tayler, The Music of Some Indian Tribes of Colombia)

Contact sheet of photographs taken on Río San Juan featuring Donald Tayler writing, behind him, Nestor Uscátegui, ethnobotanist specialised in narcotics and stimulants among the tribes of Colombia; maloca scenes and unnamed Noanamá people.

Part 14 – 00:56:19 – [British Library reference number C207/3, excerpt]

Excerpt from tape; full recording available online

Jew's harp songs recorded in La Guajira, Colombia

Part 15 – 00:57:31 – [British Library reference number C207/8, excerpt]

Brian Moser and man speak about how to operate recordings levels on Nagra reel-to-reel tape recorder

Part 16 – 00:59:08 – [British Library reference number C207/2, excerpt]

Excerpt from tape; full recording available online

Unnamed guitar melody – Recorded in unknown location

REFERENCES

MOSER, B & TAYLER, D. (1963): “Tribes of the Piraparana” Geographical Journal, 129, 4, 437-49. London.

MOSER, B & TAYLER, D. (1965): The Cocaine Eaters London: Longmans

TAYLER, D. “The music of some Indian tribes of Colombia: 1. Mountain people of northern Colombia” Recorded Sound, No. 29-30 (Jan.–April 1968)

TAYLER, D. “The music of some Indian tribes of Colombia: 2. Mountain people of northern Colombia” Recorded Sound, No. 31 (July 1968)

TAYLER, D. “The music of some Indian tribes of Colombia: 3. Mountain people of northern Colombia” Recorded Sound, No. 32 (October 1968)

The Music of Some Indian Tribes of Colombia – The Music Collections of the Anglo-Colombian Recording Expedition 1960-61 (Moser-Tayler Collection) British Institute of Recorded Sound, BIRS MCI-3 (British Library reference – 1LP0154963)

Music of the Tukano and Cuna peoples of Colombia Recorded in Colombia, 1960-61 by Brian Moser and Donald Tayler, digitally re-mastered in 1987, Rogue Records, National Sound Archive, NSA 002 (British Library reference – 1LP0159232)

***

Follow the British Library Sound Archive (@soundarchive) and the British Library's World and Traditional Music activities (@BL_WorldTrad) on Twitter.